HAILE GERIMA Nominated by Ashenafi Semu

HAILE GERIMA Nominated by Ashenafi Semu

Haile Gerima is an Ethiopian filmmaker who has been living in the United States since 1968. He went to the US from his native Ethiopia, to study acting and directing at the Goodman Theater in Chicago, Illinois. He later transferred to the Theater Department at UCLA where he completed the Master's Program in Film. He then relocated to Washington, DC, to teach at Howard University's Department of Radio, Television, and Film where he influenced young filmmakers for over twenty-five years. Inspired by UCLA classmate and filmmaker Charles Burnett, and by the celebrated Black poet and educator - Sterling Brown - Haile's films are noted for their exploration of the issues and history pertinent to members of the African Diaspora, from the continent itself to the Americas and Western Hemisphere. Often corrective of Hollywood versions of slave stories, his films comment on the physical, cultural, and psychological dislocation of Black peoples during and after slavery. What distinguishes his films are that the narratives are told from the perspectives of Africans and members of the African Diaspora itself, rather than being sanitized and misinterpreted by more commercially oriented filmmakers. His unique filmmaking aesthetic is coupled with a personal mission to correct long-held misconceptions about Black peoples' varied histories throughout the world; for this reason, he is considered by colleagues and students alike to be a master teacher in the classroom and behind the camera.

He directed, produced, wrote and edited several films. His best known film – many say – is Sankofa - which is about slavery and was produced in 1993. His most recent film is Adwa release in 1999 which is a documentary about the Battle of Adwa - the important battle in which Ethiopians defeated the Italian colonial force. His films are more about education than entertainment, and substance than style. He is perhaps the only Ethiopian to have reached the level that he has in the international filmmaking industry. And many generations of Ethiopians will no doubt follow his lead to tell the many aspects of Ethiopian stories using the medium of film.

CINEMA

INTERVIEW BY ROBERT WIREN

LES NOUVELLES D'ADDIS

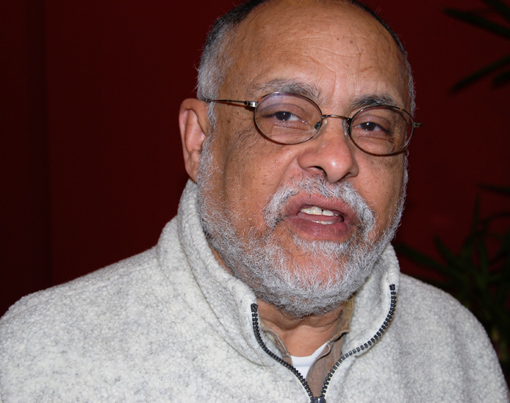

Haile Guerima,

photo Robert Wiren, Les nouvelles d'Addis, 2008

(Amiens, north of Paris, November 10th 2008)

Les nouvelles d'Addis. – Under what circumstances did you leave Ethiopia ?

Haile Gerima. It is the usual, education, to go to school. And somehow no return. So it is the usual. Especially at the time I went to school, everybody went and came back.

LNA. – When you did not come back, was it merely because of the economic situation for a film maker, that there was no issue in Ethiopia at that time or was it because of the political situation already ?

HG. – It is many different situations. It depends. I think in my own case one can say the political, the other could be there is no film industry. But those are not the reasons. It has a lot to do with my incapacity to readapt in my own birth place. That is really fundamental. Wether it is politic, economic or even just the idea of beeing unable to cope with poverty could be cause. But at this historical moment I find myself unable to resettle..

LNA. – So as often in life, it is not 100 % a personal choice. It is how things evolute and you have to adjust.

HG. – You know, there is a personal choice. The choice basically could be the choice of a famliy, the choice of professional occupation. The fact that I teach in the United States. But it is not only this. It has a lot to do with alienation also. When one transgesses, when one departs from the very origin of one settlement many things are set in motion. Within the historical circumstances those are cultivated and everything else informs that basic issue what I call intellectual alienation.

LNA. – Even if there is a choice of you would you consider yourself as exiled ?

HG. – Yes. Self-exiled. Not necessarily....As I said the historical circumstances all contribute within my own character, my own traits. It could be I cannot accept the types of government, I cannot accept the kinds of conservative social context or to be unable to express oneself, etc. Not that I am better off in the United States. I am not. I do not like the weather. I do not like the climate. I do not have money there. I do not get money from my films in America and mostly cultivate in very long terme European finance. It is just the fact that nobody cares about me in the United States to take me as a threat or as a formidable ennemy or... In our third world countries the problem was mostly that intellectuals like me were fundamentally cowards. I am unable to cope with all kinds of the lack of liberty, not from government only, individual, social, etc.

LNA. – Has your personal experienec something in common with the story of Anberber ?

HG. – Yes it informs it. It is not biographical but at least my perspective of the situations I faced, in a remote way, or other intellectuals who have been in the same circumstances. That informs the narrative, basically everything about my life or people I came across in Europe or Africa or at home, the many displaced intellectuals from Africa who live in Europe and America. All this has a lot to do with informing me towards the narrative of Teza.

LNA. – The hardships of the main character are so intense that one could think that your film is rather pessimistic. Then hope is restaured with the birth of Tesfaye and when Anberber starts teaching the children. Nevertheless this hope is very fragile, is not it ?

HG. – Well, the long distance hope is not fragile. It is really historical. In the long term there will be generations who will come who will not have to be faced with the things we are facing now. And so for me, I think, in the immediate situation it is not pessimistic per se. It is basically, I would consider, realistic for any intellectual who has to face in a return home the political and social reality of our countries, has to understand it is harsh, it is not forgiving, in many cases it is deliberate, this facts have to be known for people like intellectuals to return home. That is to me very important. An the other part of it is not because there is better home. You can live ine Europe or in Africa but you have to live somewhere.

LNA. – In Teza Anberber witnesses and experiences violence. During the Derg period violence was part of a political process. On the other hand the attack against Anberber in Germany is pure racialist hatred. Would you say that regardless the motives, violence is the same dark side of humanity ?

HG. – Yes. It darts anywhere. What I am trying to say here is at this historical moment the evil against the black race is not particularly specific but to non-whites in Europe the violence of all kinds of frustrations manifest on the socially demonized characters in television, in films, etc. Specially black people of Africa in Europe or America are demonized in the cultural climate, especially in the mass media. They are the targets of the problem of any European who is not enlightened. Any unenlightened Europeans, even enlightened Europeans, their biggest program is foreigners. They make it as if it is the principal. If the foreigners disappear coming from Africa and Asia, etc. the world would be better. But it is a scapegoating and when society scapegoats certain people then the unenlightened section or I would say the group that feels powerless, strikes back in a very incoherent way, incoherent to the very self-perpetrators of the violence. So to me my experience of the knowldge I have of Africans in Europe or America in the kind of sudden attack they receive through racial prejudice cultivated by the climate of the mass-media in the cultural aroma, the cultural aroma of a society. They scapegoat foreigners. I mean, the United States is a very big country but it is a country made out of foreigners in general. But its agenda, the political plateform of most of politicians, until this economic crisis is usually foreigners, Mexicans. So as a foreigner I feel living in a shifty place. I am not sure I will not be attacked somewhere in Hamburg or Cologne or somewhere in the United States, in certain areas. Even if people are nice, I project at least from the experience certain reality of danger, inevitable danger. One can say I will be free from this if I leave Ethiopia and live in Europe but it is proven that many foreigners have faced tragic end. And so I am not trying to romanticize. Both places are formidable circumstances for one to decide to live in. Just because Ethiopia is my home does not make it a peaceful environment for myself, able to do anything I want to do, nor does it mean in my life of exile I am spared the prejudice of that society. Both I think, especially my generation, confronts these two polarities.

LNA. – You just spoke about generation. Did you read the book of Dinaw Mengistu, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears ?

HG. – No.

LNA. – He is featuring in his novel an Ethiopian of the second generation in the States. He came as a boy. I suppose that such a character could also be the subject of a film. It is a person who knows that he has roots somewhere else but at the same time he is born or almost born in the USA. He does not know where he belongs to.

HG. I do not know the book but what you say now is real. A lot of Ethiopians of certain generations do not belong anywhere.

LNA. – We have that in France. Young people of North-African or African origin but born here facing exclusion. Well this was a nice talk with you. Thank you a lot.